As many people notice their memory deteriorating with age, and researchers have proposed a solution – a mild form of brain stimulation using weak electrical impulses. The technique can be adapted for both long-term and short-term memory, and its benefits persist for at least a month.

The authors of the study note that this is the first time brain stimulation has been demonstrated to have such a lasting effect on memory.

“This was a very brief intervention that had both immediate and very long-lasting effects,” comments Marom Bixon, a neuroengineer at City College of New York who was not involved in the study.

“More research is needed, but if it works, it could be in every doctor’s office … and eventually it could become something that can be used at home,” he adds.

Electric Brains

The study leader is Rob Reinhart, a neuroscientist at Boston University. He studies neural networks in the context of functions such as cognition, attention and memory, and their apparent deterioration due to age and as a result of certain disorders.

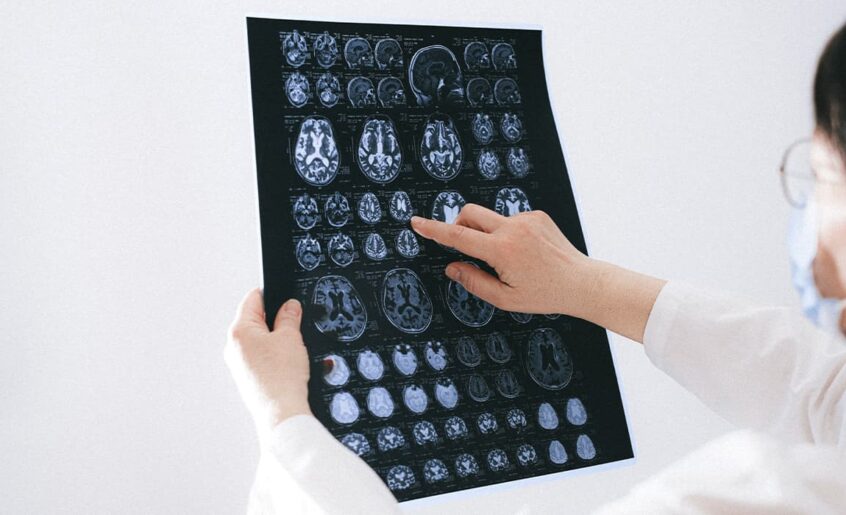

Brain cells communicate with each other through electrical impulses, and neural networks and brain regions have their own impulses of electrical activity. There is now growing evidence that applying electrical stimulation to neural networks can affect how they work and potentially strengthen connections between brain regions.

To find out if this approach could improve memory, Reinhart and colleagues used a form of brain stimulation called transcranial alternating current stimulation (tACS). It sends weak electrical pulses to the skull through electrodes that are embedded in something like a swim cap.

The doses are too low to trigger the brain cells. “These are noninvasive, safe, extremely weak levels of alternating current,” Reinhart says.

The researchers used a modern form of high-definition tACS, which allows them to target small areas of the brain. The team decided to focus on two areas known to be involved in memory: a part of the prefrontal cortex in the front of the brain, which is involved in long-term memory, and the inferior parietal lobe, an area in the back of the brain that is thought to be involved in short-term memory.

Each is characterized by a different pattern of electrical impulse activity (brain waves). In the first experiment, Reinhart and his colleagues fed pulses corresponding to the natural rhythms of each area – high frequencies for the prefrontal cortex and low frequencies for the parietal lobe.

Tingling, itching, and warming

The experiments involved 60 volunteers between the ages of 65 and 88, who were divided into three groups.

Each participant listened to a list of 20 words and had to recall them later.

During the task, one-third of the group had their prefrontal cortex modulated, and another third had stimulation targeted to their parietal lobes. The remaining third wore a cap with electrodes but received no stimulation.

According to Reinhart, those who did receive brain stimulation didn’t feel anything serious – just “a slight tingling, itching or warmth.”

The 20-minute session was repeated for four consecutive days. During those four days, the people who received the brain stimulation improved their ability to remember words. No such effect was recorded in the others.

The nature of the improvement depended on the area of stimulation:

stimulation of the frontal lobes of the brain helped better recall the first words in a list (improving long-term memory),

stimulation of the parietal lobes strengthened short-term memory.

By the end of the four days, Reinhart said, those with brain stimulation had improved their performance by about 50-65% and remembered, on average, four to six additional words from a list of 20.

The greatest improvements were in those who exhibited worse cognitive function at the beginning of the study. This suggests that the method may one day be useful for people with memory impairments such as Alzheimer’s disease or other variants of dementia, Reinhart says.

The researchers also found that the type of stimulation must match natural brainwaves — otherwise, no improvement occurs.

So far, we can only talk about the results of observations one month after the experiment. Although the study showed that the volunteers did better at remembering the words on the list, Reinhart doesn’t know if their memory or quality of life improved overall.

Bickson admits that the results are only preliminary. For example, some “brain training” games promise to improve a player’s cognitive abilities, but studies show that players actually only play the game better and don’t see the broader benefits. However, he believes Reinhart’s approach is different.